Free shipping on all international orders over £100

The first sip of a good coffee in a Parisian café, skin scented with perfume, silk stockings: Eternal JOUISSANCE muse Anaïs Nin took great pleasure in seeking such “beautiful and good things”, adorning her creative space with beautiful objects and making time for little luxuries, daily rituals that would make life feel that bit more extraordinary. A diarist for decades, freely documenting her secret desires and impulses, exploring the edges of her relationships – both with herself and others – she was also, perhaps unsurprisingly, a letter writer par excellence.

'The Love Letter' by Jean Honoré Fragonard

There is a sense of drama that arrives with a hand-written letter – a private keepsake created solely for its recipient and not intended to be shared with anyone else. A secret, signed, sealed and delivered. What a gift for a writer to see ink or smell traces of fragrance on the page meant for their eyes only. As Gustave Flaubert wrote to the poet and his “dear little mistress” Louise Colet (said to have inspired his 1856 masterpiece Madame Bovary): “I look at your slippers, your handkerchief, your hair, your portrait. I reread your letters and breathe their musky perfume.” Whether Colet specifically spritzed her notes with perfume – a ritual we wholly encourage – we’ll never know, but it does highlight a heightened sensorial experience upon reading. As Edith Wharton beautifully wrote on the joys of being on the receiving end of a love letter: “the first glance to see how many pages there are, the breathless first reading, the slow lingering over each phrase and each word, the taking possession, the absorbing of them one by one, and finally the choosing of the one that will be carried in one's thoughts all day, making an exquisite accompaniment to the dull prose of life."

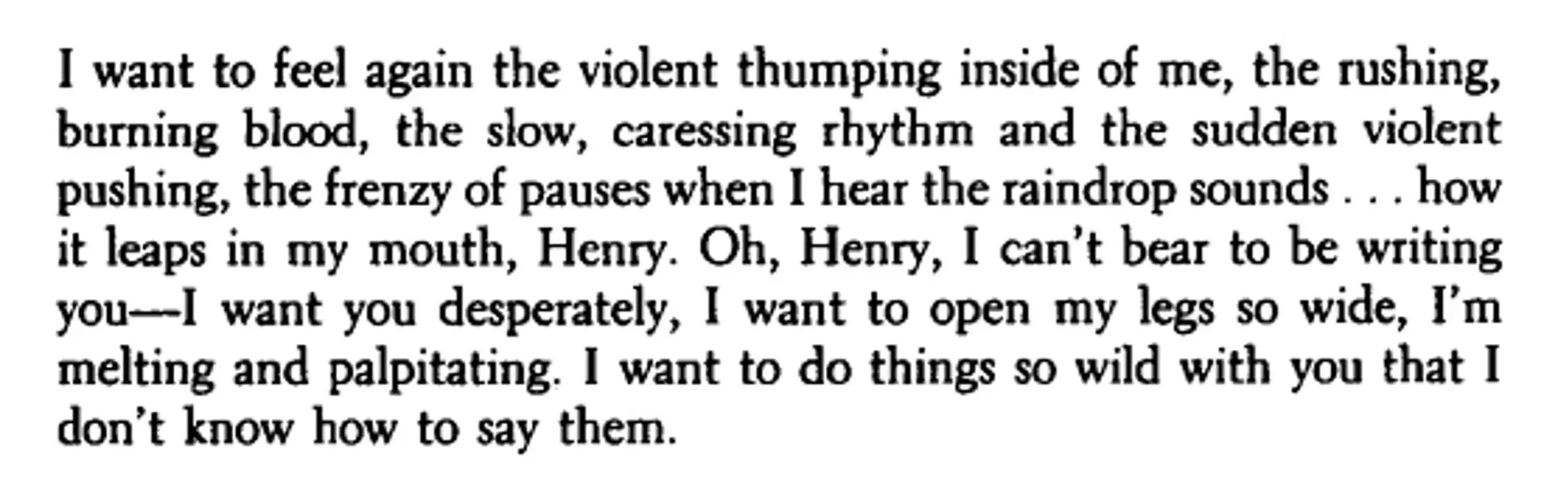

After first meeting in Paris in 1931, Anaïs Nin and Henry Miller – both married at the time – exchanged passionate letters throughout the decade, full of desperate urgency. Henry writes to Anaïs: "Anais, you have become so vital a part of me that I’m completely upside down, if this means anything. I don’t know what I write – only that I love you, that I must have you exclusively, fiercely, possessively." Amongst these intensely worded displays of affection, there is also a hunger to invite the other into daily life — years stretching with long, literary ramblings that set the scene, recount idle days, ask for money, and describe books read, dreams had, and ideas half-formed.

Nin returned such effusive appreciation for Miller’s works in progress: “there is a spiral, in you, in your book. Rich, richer than any writer or man yet known to me.” These private notes reveal two artists entwined in a profound intellectual seduction. In love with each other but above all, in love with each other’s words. Similarly, in Quiet Moments in a War: The Letters of Jean Paul Satre to Simone De Beauvoir 1940-1963, Sartre’s letters reveal a sense of his total devotion to De Beauvoir and the power of her text. “My darling Beaver,” he writes. “Two enchanted little letters from you today. Enchanted and enchanting...”

Letter from Anaïs Nin to Henry Miller in 1932

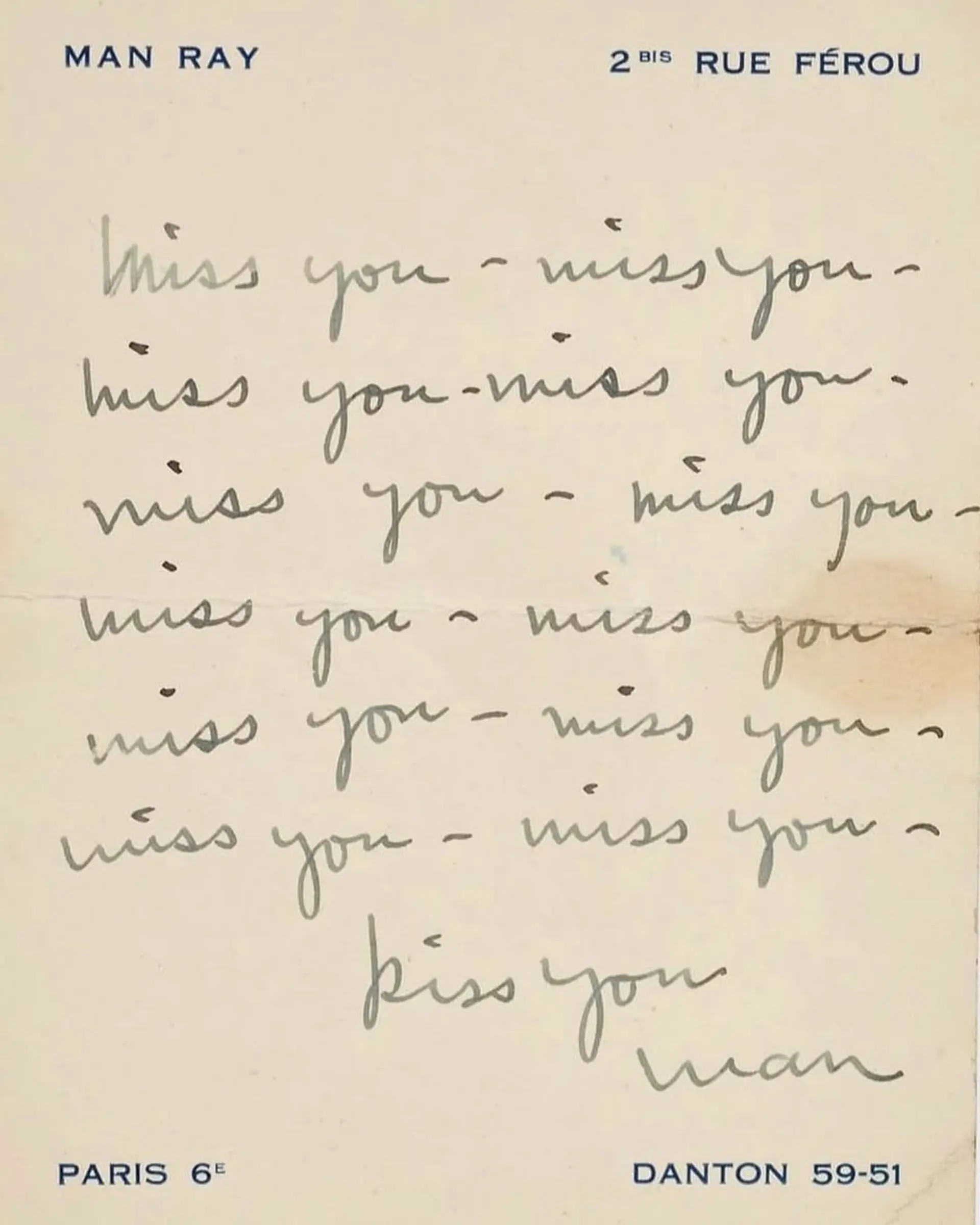

Rather than springing from a rapturous union, love letters exist precisely due to distance. It is separation, one's lover's inaccessibility, that moves ink to transfer onto paper. There’s the short and sweet style adopted by Man Ray, writing to Lee Miller from his home studio, featuring 10 scribbled "miss yous" and signed off, simply:

Man

Letter from Man Ray to Lee Miller

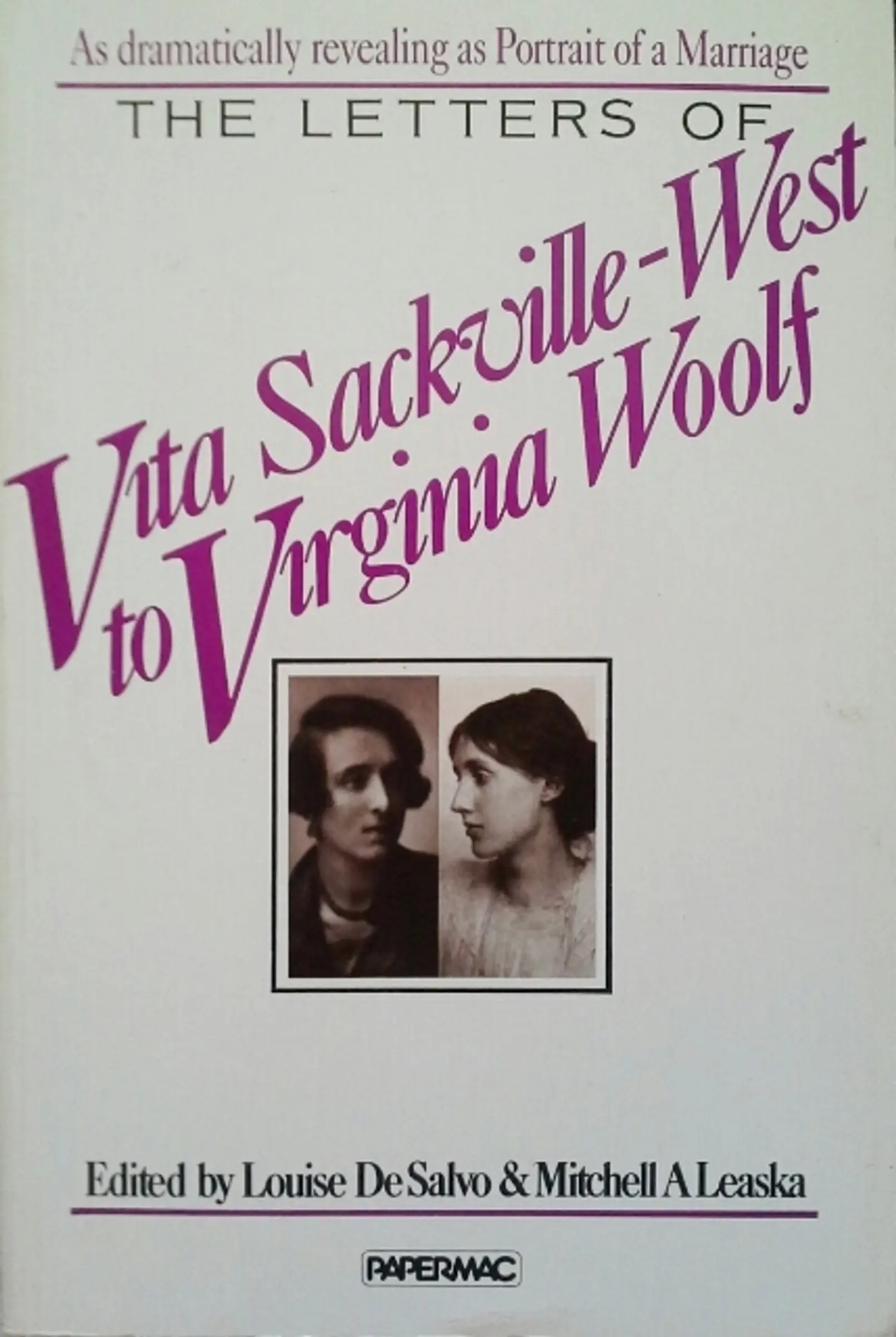

Elsewhere, letters between Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf serve as proof of their unfurling intimacy in the mid 1920s, along with West’s unguarded pent-up frustration, exposing her desire to be in the same room as her beloved.

Thursday, January 21, 1926

I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way. You, with all your un-dumb letters, would never write so elementary phrase as that; perhaps you wouldn’t even feel it. And yet I believe you’ll be sensible of a little gap. But you’d clothe it in so exquisite a phrase that it would lose a little of its reality. Whereas with me it is quite stark: I miss you even more than I could have believed; and I was prepared to miss you a good deal. So this letter is just really a squeal of pain. It is incredible how essential to me you have become. I suppose you are accustomed to people saying these things. Damn you, spoilt creature; I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this—But oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly. You have no idea how stand-offish I can be with people I don’t love. I have brought it to a fine art. But you have broken down my defences. And I don’t really resent it …

Please forgive me for writing such a miserable letter.

V.

In Antonia Fraser’s 1970s anthology Love Letters, the author dedicates an entire section to rejection. A universal, if heart-breaking, side-effect in one’s attempt to find and hold onto love is the risk that we will lose it. Loss is a part of love’s makeup, the less rosy side. Fraser opens this chapter with an excerpt from Jean Rhys’s Voyage in The Dark, when Anna receives a letter from her lover’s friend, Vincent, informing her that Walter is sorry but wishes to end their affair. It closes with one of literature’s most devastating PS's:

Photograph by Malcolm Lewis, from Antonia Fraser's Love Letters anthology

The enduring charm of a love letter is that it asks nothing in return – it can be read without reply. It is a record of feeling. An object that contains memories, promises and the simple romantic gesture of reminding someone they were in your thoughts today. Which is not, as Nin points out to Miller, the same as being beside you today. “Did you mind what I wrote you yesterday? So much literature, so many ideas, which cover up without replacing the human moments when we sit in a café without talking, and I lean my head on your shoulder and say: I don’t want to go home now Henry.”

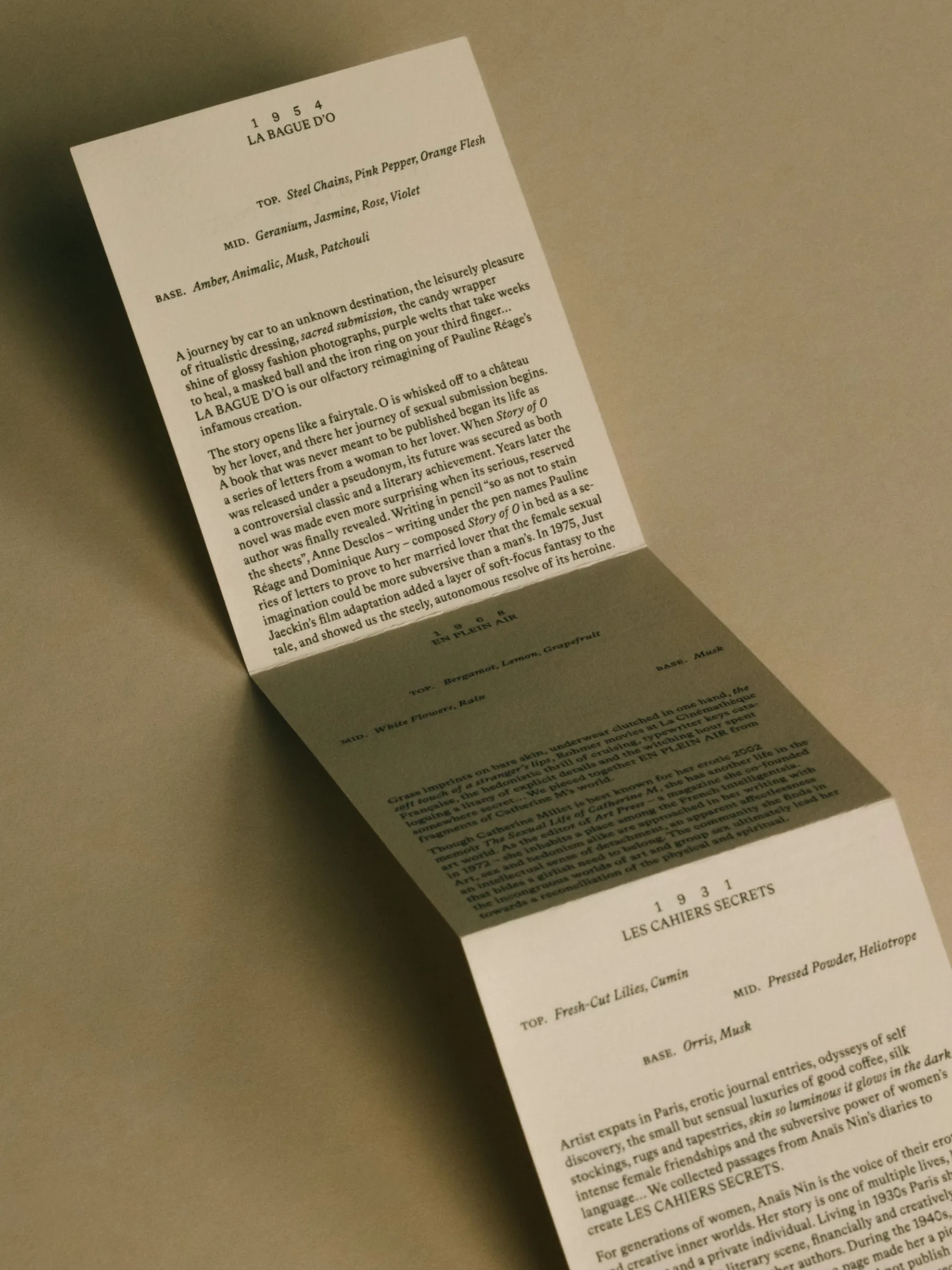

Discover our debut collection, inspired by the lives and creations of three elemental erotic writers.

"It was while writing a Diary that I discovered how to capture living moments," Anaïs Nin wrote. "In the Diary I only wrote of what interested me genuinely, what I felt most strongly at the moment, and I found this fervour, this enthusiasm produced a vividness which often withered in the formal work. Improvisation, free association, obedience to mood, impulse, brought forth countless images, portraits, descriptions, impressionistic sketches, symphonic experiments, from which I could dip at any time for material."

In tribute to Anaïs Nin, one of our foremost inspirations for Jouissance, our DIARY captures our most treasured moments, our obsessions and preoccupations, our research and the lessons we learn, and the work of our cherished friends and collaborators.