Free shipping on all international orders over £100

In this muted month of blisteringly cold weather and bare bank accounts, there’s little to do but stay indoors, reading (and inhaling the musty scent of) the vintage books you bought from the JOUISSANCE bookshop. This month’s Diary entry is a perfect companion to our bookshop edit, Tokens of Lust. Guest writer MPS Simpson muses on the pull of vintage erotica through the lens of a scandalous magazine from the Victorian era.

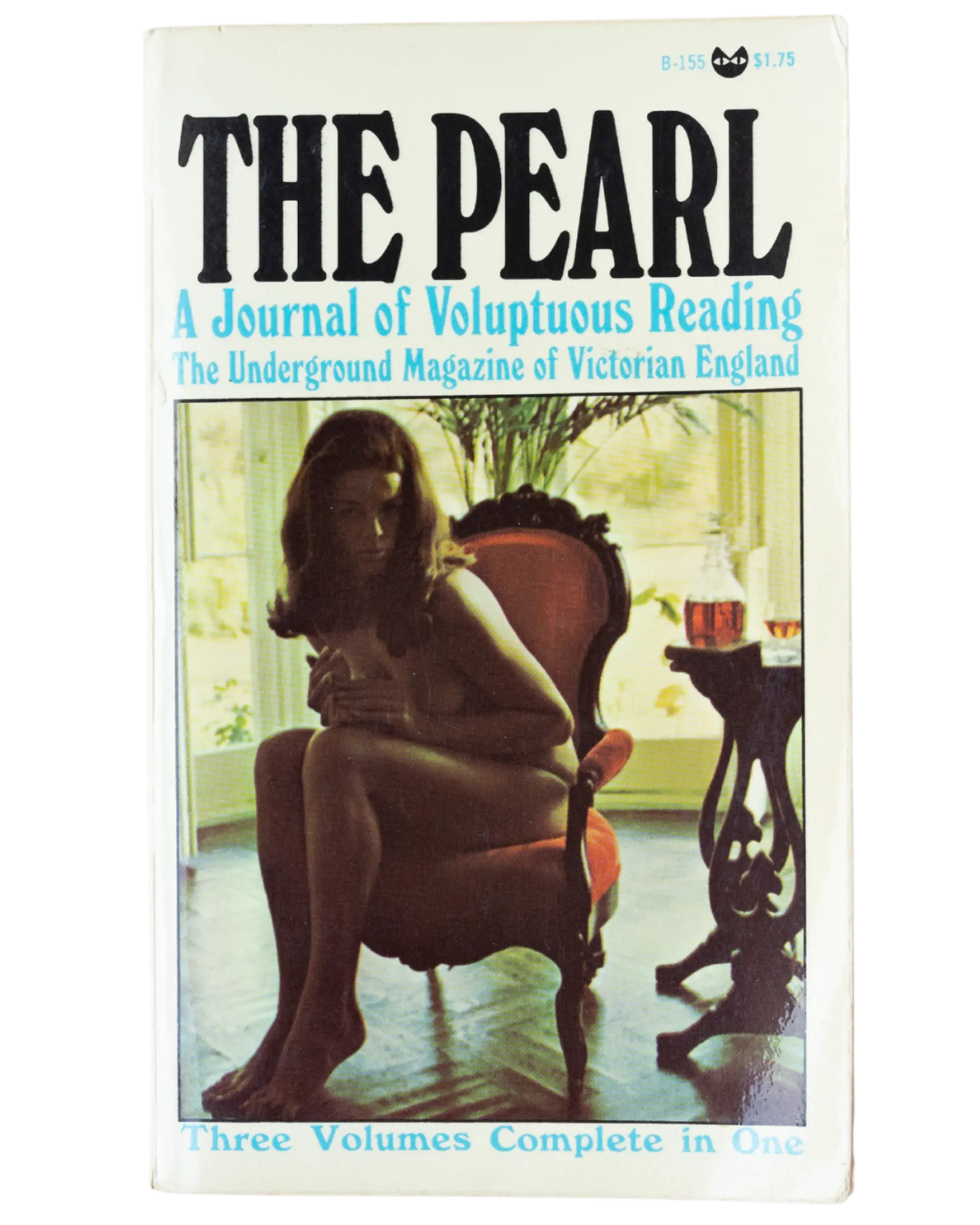

Secondhand erotica is to me what a tarot deck is to others: an object imbued with a mystical quality. The yellowing corners and bent spines feel like a sign of passage, of heritage, of communion. I love the intimacy of it, holding a book that has been held by countless hands before. Leafing through The Pearl – an erotic magazine originally published in England in the late 19th century – I try to conjure the image of its first owner and the faceless internet seller from whom I purchased it, but will never know.

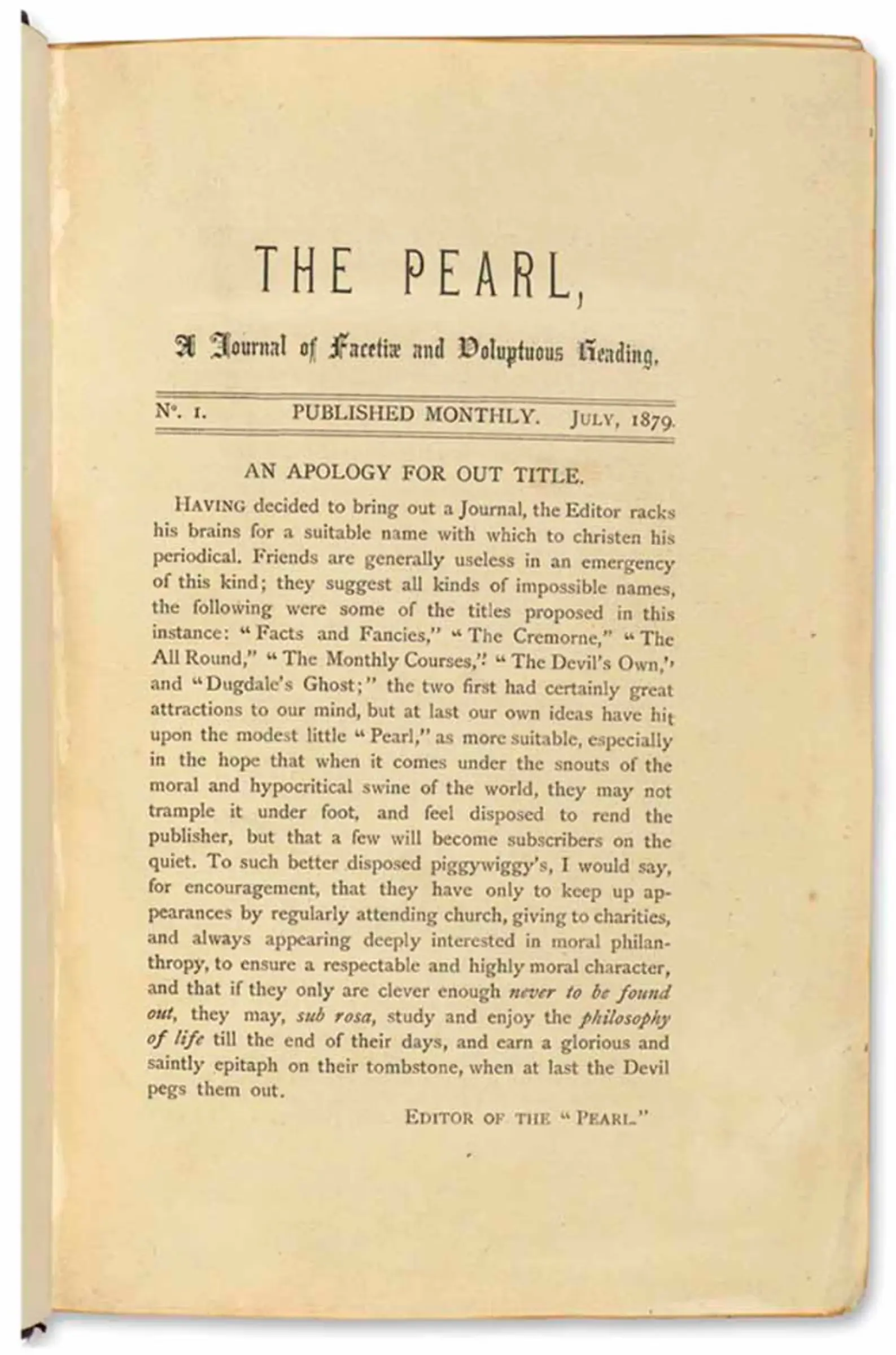

FIG I: Editor's letter from a rare second edition copy of The Pearl, sold at Christie's for £10,000 in 2014

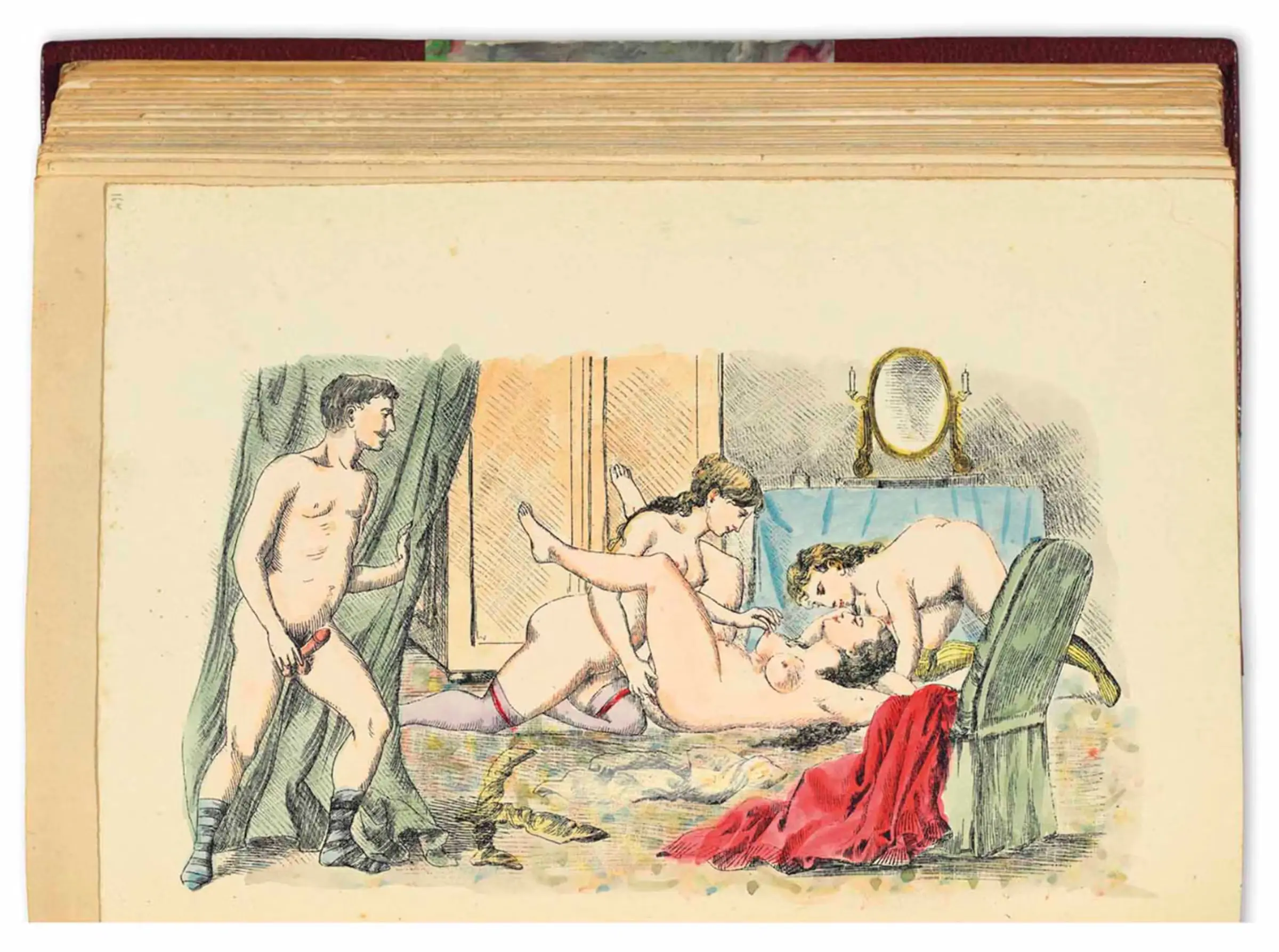

FIG II: Illustration from a rare second edition of The Pearl, sold at Christie's in 2014 for £10,000

A brief history lesson: Helmed by prolific publisher and pornographer William Lazenby, The Pearl (1879-1880) made its way through the underground channels of literary culture in the late Victorian era, titillating readers with its constellation of anonymously-written erotic tales, letters, witticisms, parodies, limericks and ballads of epic sexual pursuits. Lazenby went on to publish other erotic magazines – The Cremorne (1882), The Oyster (1883), and The Boudoir (1883-1884) – notoriously cleaving a pathway for the emergence of English-borne decadent erotic literature. No other author, aside from Lazenby, has ever been specifically named as penning the letters published in The Pearl’s pages, though it’s been claimed the magazine was host to the homosexual writings of a fixture of decadent poetry: Charles Algernon Swinburne. The rumour is impossible to verify, but it adds to the magazine’s status as an emblem of erotic culture nonetheless.

In the most infamous display of this, in 1867, a furious mother wrote to the EDM, expressing her grief at discovering her daughter had been subject to tightlacing (the practice of fastening corsets to create the smallest possible waist) whilst away at boarding school. Suffice to say, the section was never the same: an explosion of written back-and-forths regarding the pleasures and vices of tightlacing, various treatises on the fetishistic desire for the whalebone cage, and further erotic dealings coloured the entire magazine’s legacy blue. These correspondences would blossom until the magazine’s departure from publication in 1879. All was not lost, however, with several tightlacing and flagellation tales from the EDM making their way into Lazenby’s 1881 reprint of 18th-century pornographic magazine The Birchen Bouquet.

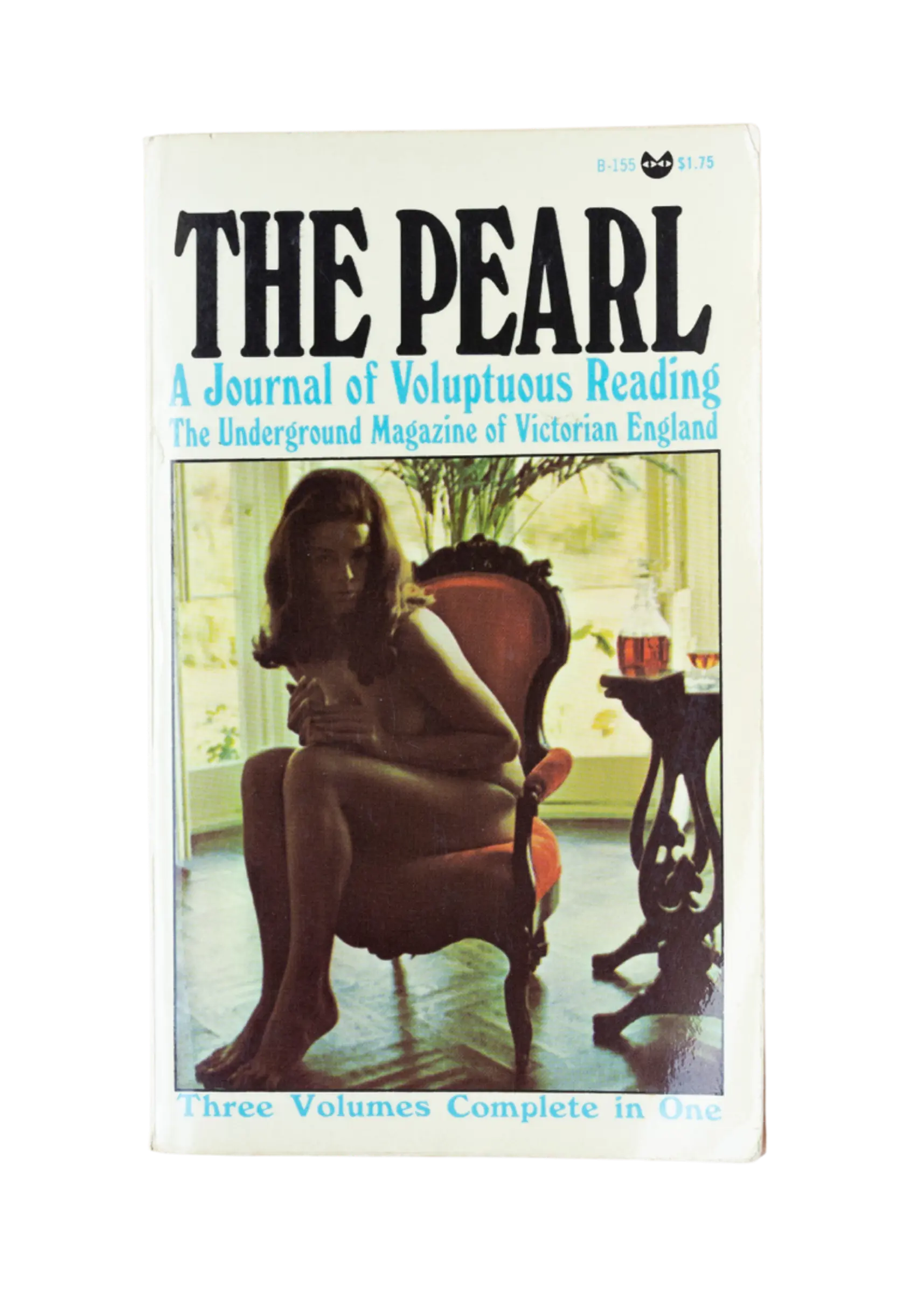

FIG III: One of The Pearl's psychedelic 60s incarnations from Ballentine Books.

The contents of the novel are fairly typical for Victorian-era erotica, ranging from the timeless – corporal punishment, flagellation, cuckoldry, voyeurism, homoeroticism – to the now-dated and uncomfortable – exoticised racism and misogyny. But it’s not the content of the erotica itself, not the lavish boudoirs nor the endless, undulating grounds of the exuberantly wealthy that catches my attention, but rather the form in which the erotica is presented. Each novel is constructed around a central conceit of memory. Miss Coote exposes her dealings with flagellation through personal letters. Lady Pokingham unveils her past sexual exploits from her consumptive wheelchair-bound present. My Grandmother’s Tale is orchestrated as a found diaristic manuscript hidden in the depths of the central character's papers, long after her death.

"We are left only with our memories of the pleasurable events – impressions of soft skin, the smell of perfume, the waves of pleasure rippling through the body."

The Story of the Eye, for instance, is orchestrated around the human drama of memory. In The Lover by Marguerite Duras, the narrator looks back on her intense and illicit affair in her teenage years. Marquis de Sade’s infamous 120 Days of Sodom is constructed around the form of a diary (or a perverted ship’s log). Memory is the connective tissue between complete selfhood and the eroticised extreme. For, in the throes of an exchange between lovers, language dissipates from our tongues and our minds, leaving our bodies through the sweat that builds up on our brows and clavicles. We are left only with our memories of the pleasurable events – impressions of soft skin, the smell of perfume, the waves of pleasure rippling through the body.

"It was while writing a Diary that I discovered how to capture living moments," Anaïs Nin wrote. "In the Diary I only wrote of what interested me genuinely, what I felt most strongly at the moment, and I found this fervour, this enthusiasm produced a vividness which often withered in the formal work. Improvisation, free association, obedience to mood, impulse, brought forth countless images, portraits, descriptions, impressionistic sketches, symphonic experiments, from which I could dip at any time for material."

In tribute to Anaïs Nin, one of our foremost inspirations for Jouissance, our DIARY captures our most treasured moments, our obsessions and preoccupations, our research and the lessons we learn, and the work of our cherished friends and collaborators.